The track, the people in the stands, the finish line — they won’t see it, but atop the medal podium, there is ample space for blind track and field athletes to feel and own that glory.

However, there are two challenges muddying the possibility. There are not many able-bodied individuals willing to come forward as aids, and likewise, many blind individuals just don’t get involved in that kind of sporting activity.

Christopher Samuda, president of the Jamaica Olympic Association (JOA), explained that if athletes are blind or have a level of blindness that impairs their ability to run in a straight line, they run with a guide. The guide can be sighted, and doesn’t really need to have any disability.

“So far, in the history of Paralympics in Jamaica, we have not had a situation where we have a totally blind person running with a guide. We are, of course, going to enter that field, because there are athletes who are blind,” Samuda, also president of the Jamaica Paralympic Association, told the Jamaica Observer.

Paralympic Games are major international sports competition for athletes with disabilities. Paralympic athletes compete in six different disability groups — amputee, cerebral palsy, visual impairment, spinal cord injuries, intellectual disability, and “les autres” (athletes whose disability does not fit into one of the other categories, including dwarfism).

“There is, of course, somewhat of a reluctance for persons to come forward, and I think that is because that has not been our experience to date. If it had been our experience, I am sure that able-bodied athletes would come forward in order to be guide for blind athletes. But once we are able to identify blind athletes with talent who would wish to pursue track and field, I’m sure that able-bodied athletes will come on board and be guides for them,” Samuda continued.

Conrad Harris, executive director of the Jamaica Society for the Blind (JSB), said it is not a matter of blind people shying away from track and field. Instead, they are left at a standstill.

“Many persons who are blind, often, we don’t have the opportunities to do sports or have an outlet to exercise and stuff like that. So because of that, it is highly likely that we could be affected by many of those lifestyle diseases that they talk about. So, anything that promotes the movement of blind persons, then we are fully in support of it. There are just not enough opportunities for persons who are blind to do independent sports, exercise, et cetera,” he told the Sunday Observer.

Reflecting on the passage of the Disabilities Act 2014, Charmaine Daniels, CEO of the Digicel Foundation, said though the Disabilities Act has guided a nationwide effort to place inclusivity, equality and accessibility at the forefront, and provides comprehensive protection of the inherent rights of persons with disabilities, many disabled individuals are still disenfranchised.

“Persons with disabilities face systems that were not designed to accommodate all people, ranging from the health-care system to employment and education. By ensuring that no one gets left behind, Digicel Foundation is the leading corporate donor to the community, with a total spend of US$10.65 million since inception,” she said.

Additionally, Harris said the efforts of the Jamaica Paralympic Association should be more widely publicised.

“It definitely needs more promotion. One of the things I wonder about, however, is if there is the capacity right now to absorb additional persons. I don’t know about that, so I can’t speak to that. But it definitely should be more widespread, because more opportunities at physical activity would really be better for us.”

Samuda agreed with Harris, noting that the involvement of blind people in track and field would also facilitate self-actualisation.

“It builds confidence, and then we educate that you are not disadvantaged simply because you are impaired of vision. That is something that perhaps you were born with… you perhaps lost your vision, but you must not consider it a disability. That is what human potential is all about; going beyond the optimal, surprising yourself and challenging yourself,” the JOA president stated.

Coming June, Jamaica will have a group of blind athletes going to the 2023 World Para Athletics Junior Championship. To be held in Paris, France, the championship will feature athletics events contested by athletes with physical and intellectual disabilities in two age groups — under-20 and under-18.

Meanwhile, Samuda said there is a cadre of blind athletes who are now in training for track and field.

He pointed to the success of a local judo athlete who is blind in one eye and partially blind in the other, who started judo in 2017 and went to the 2019 Parapan Games and won a bronze medal.

He noted that there were three basic tenets at the JOA that blind athletes are encouraged to adapt to.

“One, you can create the possible out of the impossible. Two, you can create the credible out of the incredible. And three, if it is to be, it is up to me. So those three tenets, we impress upon our blind athletes, and generally, our para-athletes,” he told the Sunday Observer.

Samuda said the JOA indicates to its blind runners, by way of how they are trained both on and off the field, that they can be whatever they will themselves to be.

“What we encourage them to be, and so far they have adapted, is that they have the capacity to earn a gold medal as any able, or an athlete that has vision. So we first start with education, because you have to, of course, address that if the person is to have that confidence in self in order to perform. And then secondly, of course, we have to address the technical competencies.”

Harris interjected, saying this improves quality and length of life.

“You are extending people’s lives. The medals and stuff would be a bonus, but I think it is a matter of life and death, and how long you live on this earth. Anything to help persons who are blind to be more physical, then bring it on.”

Further, Samuda said the JOA has coaches who are involved in training athletes, some of whom train Olympians. To the best of the association’s ability, Samuda said blind athletes are given “every opportunity” that able-bodied athletes experience.

“…So that they don’t feel that they are discriminated, or that they are getting perhaps less than what the Olympians are getting.”

However, he admitted that there is always a challenge where funding is concerned as is customary across all sporting organisations. The Jamaica Paralympic Association, for which Samuda is also president, faces the same challenges.

“So what we would want to do for athletes optimally may not very well occur because of financial constraints. But we tell our athletes that despite the challenges we experience, despite the challenges of the association, we have to rise above those challenges. And we have done so admirably over the years.”

Loss of sight and their adventures with sport

Damion Rose, 39, was born with glaucoma and lost his sight completely at age two.

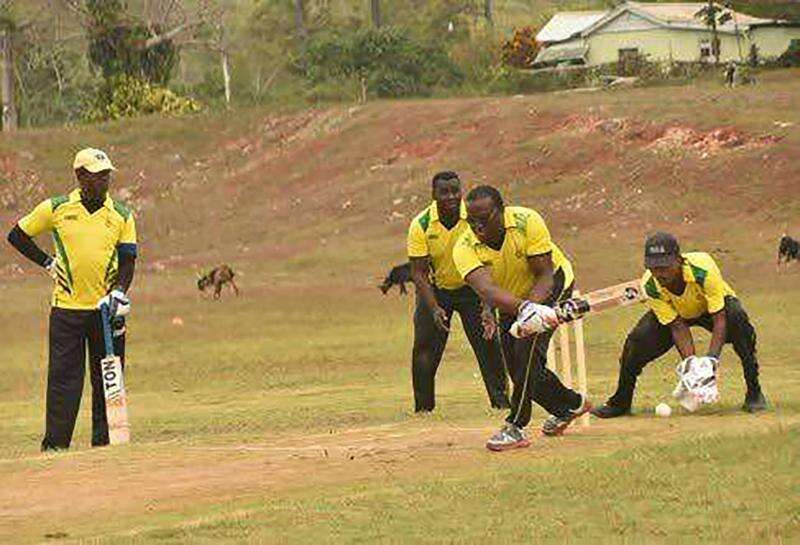

“I play blind cricket. When we were at School for the Blind, they would put up like three different ropes that are the entire length of the field. And we used to hold the ropes and run. That’s how we used to take part in sports day. We even used to do relay with the ropes. But I have never thought about doing track and field professionally. That would be too much work.”

Sharmalee Cardoza was born blind. She is the mother of a 10-year-old daughter.

“I did swimming at the School for the Blind and I also went to The University of the West Indies (UWI) and I swam for my hall at an inter-hall game. But I never really continued it.

Robert Ball, 33, is a father of four who lost his sight in 2017.

“I have not thought about anything sports-related since I went blind. I was a baller and I used to play football before, but after losing the sight I don’t play anymore. I remember when I was at Jamaica Society for the Blind and we had a fun day and we raced. But they set up a chord above our waist, so that we can hold it and run. That guides us. Other than that, if I even want to hurry in a room, I slightly run. It would be more of walking speedily, but you have to know the place. And I will still bump into something because I am not perfect.”

SAMUDA…we have not had a situation where we have a totally blind person running with a guide

DANIELS… many disabled individuals are still disenfranchised.

and then

and then